"Making something out of nothing, or precisely, luring something from the unconscious and giving it material form is the closest thing to real magic there is in this world." (art critic Michael Bonesteel)

*by Barbara Lee Smith

There is magic in the art and life of Judith Scott. That she is even making her powerful forms is a happy ending to the grimmest of fairy tales. Like any good story, these forms provoke other stories. Here's mine: In the late eighties, I was working on a book about contemporary embroidery. I was working in the winter in a house in the woods near the western shore of Lake Michigan, just the dogs and me, and I was discouraged. I was struggling, not sure if I could do justice to the artists I was profiling. So I went for a walk on the beach--where I discovered a mighty rolled-up pile of rope and net, mixed with sand, sticks, and fishing lures, a bundle from the sea. I hung this "sculpture" on a nail on a piling, and it remained there as a talisman urging me back to work.

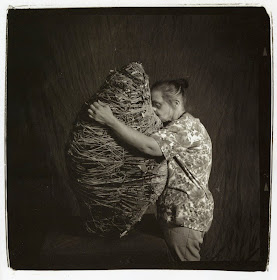

When I first saw photos of Judith Scott's forms, I recalled that moment and felt that I "knew" these works. I saw "Metamorphosis: The Fiber Art of Judith Scott" last fall at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago. I'm not alone in having a strong response to her work. Those who come in contact with it have the urge to hold it, pat it, or somehow interact with it. The forms are simple, cocoonlike, suggesting the human form; they bulge in all the right places.

|

| Judith Scott (1943 - 2005) |

The urge to make associations with her work is almost unavoidable. Just for starters, they are bundled, wrapped, enfolded, sheltered, clothed, enveloped, and bandaged. They are also tough: raw, knotted, controlled. They are made slowly with accretions of "found" materials wrapped in place, much as a spider encases a fly in her web.

These found materials, to put it bluntly, are mostly stolen, or "appropriated," to use proper art-speak. But art-speak is inappropriate for discussing Scott's work. We can't begin to know what is going on inside her, for not only is she profoundly deaf, she doesn't speak, and she is also developmentally disabled, having been born with Down's syndrome almost 60 years ago. She has been making these forms for less than 10 years, but her "body of work" - certainly an appropriate term - is large and growing. It is large enough for a touring solo exhibition of her work; a handsome book/catalogue about her and her work, written by John MacGregor; and a delightful video that focuses on her, The Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, where she works, and her twin sister, Joyce Scott.

Her story is the stuff of novels. Joyce and Judith were born in 1943 in Ohio. Joyce, older by moments, was expected; Judith was a surprise to her parents and the doctor. They joined three older brothers and were absorbed into an active family. As twins, the sisters were very close and lived, played, bathed, and slept together until they were seven. Joyce writes in Outsider Magazine, published by Intuit: "At first we lived unaware and unafraid. In the sandbox where we played, pouring sand in each other's hair, wiggling toes in wetness, making our leaf and stick dishes and dinners, we still felt only the innocence of our soft skin and earthy explorations. But the forces pulling at us and threatening us grew as we grew. No longer wrapped in the protective web of our family's ties alone, we soon joined the neighborhood. There Judy was seen as different - and to a few ignorant and fearful souls, different meant dangerous. Our next-door neighbors refused to let her in their yard. Currents growing, doors slamming shut."

Joyce went to school. It was hoped that Judith could join her, even though she didn't speak. It was not known at the time that Judith had become deaf, and so testing revealed her as "ineducable." Responding to the currents of the time, her parents placed her in a state institution. It was probably no better or no worse than typical institutions in the fifties, but it could have been the end of the road for Judith.

The effect on her family was profound. Joyce remembers waking to find a cold place in the bed next to her: Judith was gone, and Joyce hadn't been told beforehand. Then a year after Judith was institutionalized, their father had a heart attack from which he never fully recovered. Visits to Judith became less frequent over time. Joyce writes: "The State Institution was a terrible place - worse than terrible - full of the awful sounds and smells of human suffering and abandonment. It still lives in my nightmares. That Judy is not haunted, that she has not been destroyed is a testament to the human spirit and most especially to hers. There is no doubt that institutional life has left its mark. Her habit of stealing small bits and pieces, of hoarding things, of being initially suspicious of strangers and of tending to isolate herself, these all reflect those terrible times. Her incredible ability to persevere and to sustain her focus, to hear her own inner voice, may also come from those years of crowded aloneness."

Joyce moved to California, had a family, and divorced. In 1985, she attended a retreat and "found myself knowing with absolute clarity that it was both possible and right for Judy to live out the rest of her life near us; for us to be together again." A long legal process ensued, with Joyce becoming Judith's conservator and Judith heading to California. One last act of "institutional neglect," Joyce writes, was that Judith was loaded on a plane alone to make the flight from Ohio to California. Once Judith recovered from this trauma, though, her reunion with Joyce and her family was extremely happy. Joyce found a group home for Judith to live in and took advantage of California's state program through which all disabled individuals have the opportunity to learn.

It was through this program that Judith Scott went to the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland. Here is a magical place, but this magic is the result of immense dedication. Training for independent living and preventing institutionalization are included in its goals, as well as fostering the artistic development of its clients. Clients work with professional artists in programs that include drawing and painting, woodworking, rug hooking, ceramics, and fiber.

Scott didn't fit in at first. She didn't draw and wasn't interested in painting. In late 1987, however, she began to attend a class taught at the Center by textile artist Sylvia Seventy. Most of the group was doing needlepoint, but that wasn't for Scott, either. There was a box of sticks in one corner of the room, and Seventy remembers Scott starting to steal the sticks and wrap them in yarn. She was on her way. John MacGregor writes in his book: "Clearly incapable of conforming to expectations, of following instruction, or imitating what the other students were doing, she simply invented something totally new."

Like her first work wrapped over sticks, some of Scott's forms are long and resemble the body. Hung vertically, they remind one of Giacometti figures. Others are cocoonlike bundles and balls. She adds objects picked up on what the staff refers to as her "shopping expeditions." (Car keys have been known to disappear into the maw of Scott's wrappings.) To deconstruct one of her sculptures would be like an archeological dig - discovering what was available during the particular time she made it. Cones emptied of yarn, parts of an electric fan, a wheel, pieces of cardboard from the client who works next to her all alter the shape. Scott is protective of her finds, hoarding them in bags beside her chair. She works sitting down with the sculpture growing on a table in front of her, shifting it when necessary to reach its opposite side.

She is a tiny woman - just 4 feet, 9 inches. These works become her size as they grow. When we met, she regarded me with a slightly askew expression and a glint in her eyes. She allowed me to shake hands, with a soft handshake, but she obviously wanted to get back to work, so I visited for only a few moments. Tom di Maria, the director of the Creative Growth Art Center, signed to her the word "beautiful," a gentle circling of the face, and she smiled and signed the same back to him. Then she gave us both a thumbs up, and we waved goodbye. Di Maria told me that when she finishes a work, she brushes her hands together to signify completion, gives the work a pat, and goes on to something new.

There are many ways to approach these works. John MacGregor makes a powerful case for a psychoanalytic interpretation and places them within an art-historical context. His book about Scott is well worth studying.

As a maker, I appreciate the powerful effect on the artist of the rhythmic repetition in wrapping; it has hypnotic, obsessive appeal. It is a sensual pleasure to feel the yarn glide through the hands, but it is also tough to work for long hours every day. Scott is bothered by abrasions on her hands from pulling on the yarn, and she uses Band-Aids whenever she has access to them. In fact, she seems to enjoy encasing her fingers with Band-Aids for more than practical purposes. It isn't a stretch to presume that she loves to be cared for after so many years of institutional neglect.

There is also pleasure in control. She is careful about knotting the yarns, keeping the unwieldy "found" objects in place as she tucks them in with yarn and fabric strips. This too is something that makers of art using fiber understand.

Scott and others in the center's workshop are actively involved in continual, pure art making, producing works that come from deep within. As Tom di Maria commented to me, "They have no audience inside their heads getting in the way of the creative moment." This is something that all artists desire and find rarely. Here there are no deadlines; no what-will-others-think distractions; no how-will-I-pay-for-the-new-roof worries; no will-this-be-good-enough-to-get-in-a-show fears. I felt at this place a strong sense of pleasure and pride as new work developed.

And I thought about the meaning of "asylum," and how it has been altered by institutional abuse so that it conveys opposite meanings - both a place to be avoided at all costs and a place of protection. Rescue and reunion are part of Judith Scott's story, but so is her indomitable spirit, which has found release in layered bundles expressive of a mystery we'll never fully comprehend.

source:

Judith Scott Artist

No comments:

Post a Comment